Hezbollah's Forgotten Propaganda TPS Video Game

Holy Defence's Unsettling Indoctrination with Disinformation

It was 2018 in Beirut. The October 17, 2019, uprising was still months away. The Ponzi scheme that would steal our money from the Central Bank—masterminded by Riad Salameh and benefiting the corrupt political elite—hadn’t imploded yet. COVID hadn’t struck. The war in Syria seemed to have settled, with Assad clinging to power thanks to Nasrallah, Putin, and Khamenei.

At 28, I was just trying to enjoy my life before it all unraveled. A dear friend of mine was flying in from a GCC country that had banned travel to Lebanon. Like all of us, they loved Lebanon, and a travel ban wasn’t going to stop them spending a fun time in Beirut. I offered to pick them up, checked their flight status, and waited near those steel barriers where countless Lebanese greet loved ones with teary eyes, those in the diaspora—those forced to visit only when they can.

When they emerged from the terminal, they grabbed my arm, and we walked outside toward the parking lot. But the second we stepped out, their grip tightened, their nails digging into my arm. They froze, wide-eyed, and blurted, “Esh haaaaad?” (What’s that?!) as they stared up at an enormous advertising banner.

There it was: a man in military fatigues, an assault rifle poised, aiming at something off-camera. Beside him, the Hezbollah logo and a bold title that read: Holy Defence.

What is it?

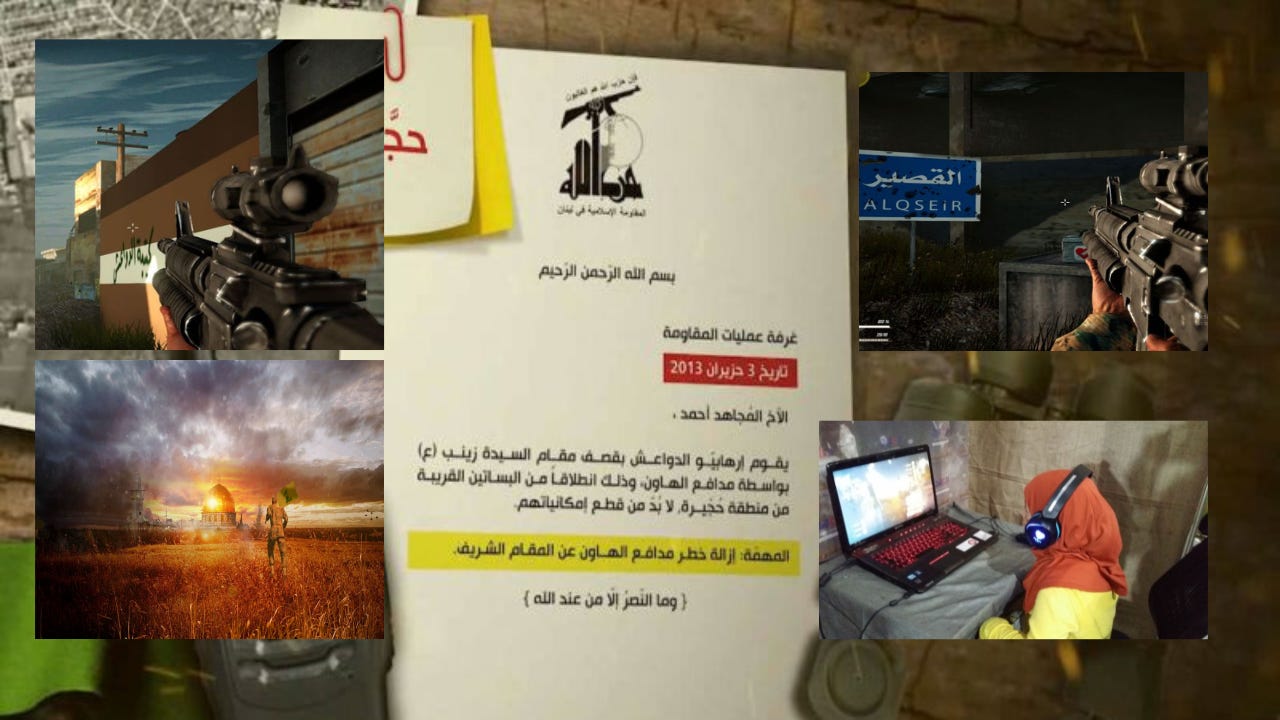

Hezbollah's Holy Defence is a third-person shooter video game developed as part of the group's propaganda and recruitment efforts. Released in 2018, the game is designed to glorify Hezbollah’s military operations and ideology, presenting players as fighters defending themselves against perceived threats, including Israel and extremist groups. It was a low-resolution fantasy game that attempted to justify Hezbollah’s catastrophic and brutal military campaign against the Syrian people to help prop up the now-fallen Assad regime.

Holy Defence isn't Hezbollah's first game, though. Their gaming journey began in 2000 with Quds Kid. After Israel’s retreat from South Lebanon, they released Special Force I, followed by Special Force II, which was based on the 2006 war between Hezbollah and Israel. It seeks to imitate the U.S. military’s own video game forays, like “America's Army” and collaborating with Call of Duty.

The game features very basic graphics for the late 2010s, not-so-immersive combat scenarios, and weapons used by Hezbollah fighters. It tries to frame the group's actions as heroic and legitimate, while promoting its narrative of resistance even when Hezbollah became the aggressor in Syria, and strayed very far from its resistance to Isreal claims.

Targeted primarily at youth in Lebanon and across the region, Holy Defence was once a digital extension of Hezbollah's broader media strategy to solidify its influence and recruit support among its base.

The fictitious scenarios only further entrench sectarian divisions and normalizes violence under the guise of defense. With the player, Ahmad yelling “Labbayki Ya Zeinab” before throwing a grenade. Yikes.

Here’s a contemporaneous report in English on Iranian TV:

Here’s one aired in Lebanon:

The Game Intro:

7-Minute Gameplay Video I Compiled:

I didn’t blink when I saw the Holy Defence ad. It didn’t strike me as odd, or even worth a second glance. At that point, I had lived through years of Hezbollah’s imagery and propaganda dominating public spaces.

Billboards with “martyrs”, slogans of “resistance,” and photos of armed men had become part of the urban landscape, as unremarkable as graffiti on a wall. But when my friend dug their nails into my arm and gasped, their horror felt like a jolt of electricity. I was suddenly aware of how deeply desensitized I had become to the absurdity and brutality of what I was looking at. Their reaction—a mix of fear and disbelief—reminded me that there was nothing normal about a video game full of lies and incitement, glorifying terror and violence by Hezbollah on a Syrian people that simply wanted to be free. And that ad, splashed across an airport parking lot for all to see the second they step into the country. Like a reminder that you’re under Hezbollah’s mercy now (thankfully no more!)

Their shock dragged me back to the reality of how fucked up this was. Holy Defence wasn’t just a game; it was a carefully crafted piece of propaganda designed to shape young minds, to glorify killing, and to rewrite the narrative of Hezbollah’s intervention in Syria.

It wasn’t about protecting Lebanon, as the group often claimed—it was about spreading its influence and serving the agendas of Tehran and Damascus. And yet, even I, someone who once prided themselves on questioning these narratives, had become numb to its pervasive presence. It took their fresh perspective, untainted by the slow creep of hpyernormalization, to remind me that the propaganda machine had sunk its claws so deep, that many people were never even aware of 10% of the horrors Hezbollah had inflicted on civilians in Syria…

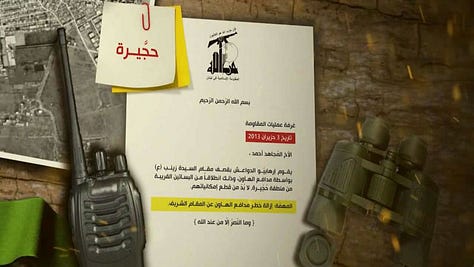

What struck me most was how far you’d have to go down the rabbit hole to believe the lies that games like Holy Defence and banners like these tried to sell. Take, for example, Hezbollah’s oft-repeated justification for its intervention in Syria: the supposed attack on the Sayyida Zainab shrine in Damascus. It was the rallying cry that framed their military involvement as a sacred duty, a defense of Shia holy sites.

Yet, the story crumbled under scrutiny. Timour Azhari, a Reuters journalist, posted a video of the shrine after the Assad regime was overthrown—sparkling, pristine, untouched by any sign of destruction. The so-called defense of the shrine was nothing more than a pretext, an emotional manipulation to justify their actions and sideline any dissent. Yikes.

Today, with Assad no longer in power, Hezbollah defeated in Syria, and significantly weakened in Lebanon, it’s crucial to reflect on the deeply problematic legacy they’ve left behind. The justification of senseless violence, force-fed to people through propaganda, rhetoric, and even video games like Holy Defence, has left scars that will take generations to heal. These narratives weren’t just political—they were designed to normalize brutality, glorify conflict, and stifle dissent by framing war as a righteous, inevitable cause.

The use of tools like video games to indoctrinate youth reveals the extent of their manipulation. It’s not just about what happened on the battlefield but about the ideas that were seeded in the minds of a generation. Games like Holy Defence didn’t just entertain—they distorted reality, creating a fictional world where violence was valorized and alternative perspectives were erased. The legacy of this indoctrination remains a barrier to peace and reconciliation, perpetuating cycles of mistrust and division.

As we confront this legacy, it’s important to make sense of how these justifications were built—on half-truths, propaganda, and emotional manipulation. The myth of the Sayyida Zainab shrine’s attack is just one example of how pretexts were manufactured to excuse violence and foreign intervention. These fabrications weren’t harmless; they enabled a culture of impunity and allowed leaders to exploit sectarian fears for political gain.

Moving forward, acknowledging and dismantling these narratives is critical. It requires truth-telling, accountability, and an effort to reimagine a future where conflict isn’t glorified and violence isn’t the default answer. By shining a light on the mechanisms of propaganda, we can begin to rebuild a society that values peace, truth, and justice over war and lies.